COMMENTARY

by Frank Carroll May 9, 2023

As wildfires continue ravaging our nation, particularly in the 11 Western States, we must look closely at federal wildfire suppression policies in use since 2009. The “managed wildfire” approach, adopted by the Forest Service, has granted the agency power over not just the fate of our public forests but also public and private property, wildlife and their habitats, and the lives of those residing within wildfire-prone areas. This assumed authority has been exercised with no accountability.

The Forest Service has yet to report on the cumulative and compounding environmental effects of its approach to letting big fires burn. The agency may be losing the “Chevron deference” that claims the science of wildfire effects is unclear and that the rest of us should defer to their decisions. As the consequences of the policy become more apparent, we must critically examine the reasoning behind the Forest Service’s actions and question whether the current strategy is in the best interest of our environment, communities, and people.

The mounting evidence of negative wildfire effects, including persistent smoke, extensive burning, and the tragic post-fire flooding that took the lives of three individuals near Las Vegas, NM, last year, is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. As the devastation caused by wildfires continues to escalate, scientists, academics, and professionals diligently seek to understand why these fires are causing more damage and lasting longer than they did a mere decade ago.

While the Forest Service often attributes these changes to climate, a more challenging and potentially significant factor is the practice of “applied wildfire” – using wildfires, whether ignited by humans or lightning, to achieve objectives other than immediate fire suppression.

There is a certain logic behind the idea of containing a destructive wildfire by essentially encircling it with a controlled burn. This approach involves retreating to the nearest defensible ridge, constructing fire lines, and then igniting fires from those lines as a means of corralling the fire.

However, as the consequences of alternative wildfire policies become more severe, we must recognize that the current approach may not be effective, sustainable, or legal. We must carefully reassess the assumptions underpinning these strategies and explore alternatives that prioritize both the safety of our communities and the health of our environment.

The North Complex Fire of 2020 and the Black Fire in the Gila National Forest in 2022 are stark reminders of the potential for managed fire policies to spiral out of control, causing widespread destruction and loss of life. On September 6, 2020, firefighters lit an indirect firing operation on the North Complex in Northern California. On September 8, “widespread firing ops” blew up and crossed the Middle Fork of the Feather River. On September 9, the fire roared to life in red flag winds, burning 180,000 acres, two communities, and a 500-acre camp for child cancer patients and killing 16 civilians.

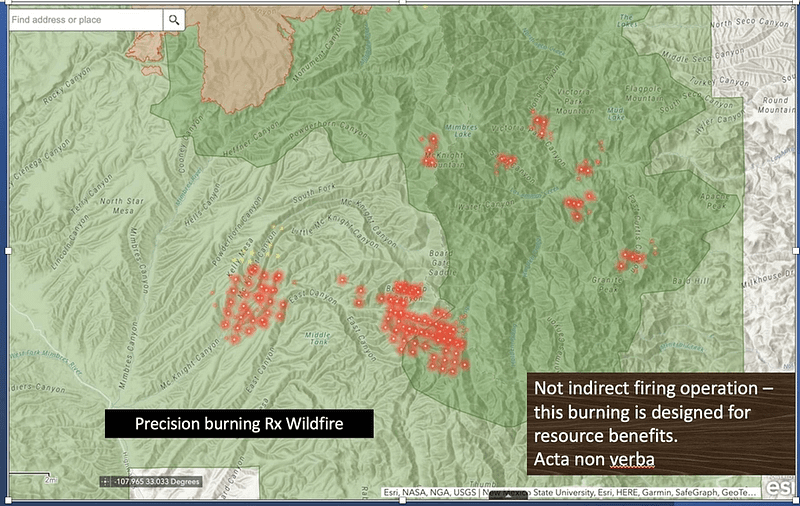

Firefighters used drones to light much of the Black Fire’s 325,000 acres. Drone-lit fires more than ten miles south of the southernmost flank of the Fire were designed to burn the entire Aldo Leopold Wilderness. The Incident Commander told Sierra County Commissioner Jim Paxon they had been trying to burn the wilderness for years. Now, they were using drones to light the fires.

The Forest Service’s failure to account for these tragedies and the lack of public involvement in decisions, including air tanker and fire-retardant use to support large-scale firing operations, underscore the urgent need for transparency and accountability.

It’s time to rethink this baffling resource management practice, this massive, premeditated burning. The government has a legal duty to warn people, to involve affected people, and to conserve our air, water, timber, vegetation, cultural uses of the forest, and so much more.

As we confront the ever-growing threat of wildfires, we must question the efficacy of current federal wildfire suppression policies and explore alternative approaches that prioritize the safety and well-being of both our communities and our environment. Only then can we hope to mitigate the devastating impacts of these fires and build a more resilient future for our nation’s forests.

Frank Carroll is a veteran of 50 years of wildland fire expertise, an expert consultant in international wildland fire practice. Frank’s years of wildfire forensics and policy analysis included 30 years in the US Forest Service. Frank can be reached at Frank@WildfirePros.com and

The Forest Advocate

Santa Fe, New Mexico